Bitcoin Academy: Part 2

The Design of Bitcoin: Bitcoin as a Network

Recap

In Part 1, we explored how money, the internet, and cryptography set the stage for Bitcoin’s invention. We also identified three major problems in the traditional financial system:

-

Money was centralized and politically vulnerable. Governments and banks could control or debase currency at will.

-

The internet hadn’t delivered financial independence. You could send an email directly, but sending money still required a bank or payment company as an intermediary.

-

Cryptography hadn’t replaced institutional trust. We lacked a way to transact value online without trusting a third party to keep the ledger.

Then came the spark: the 2008 financial crisis, which dramatically highlighted these weaknesses. In response, a person (or group of people) using the alias Satoshi Nakamoto proposed Bitcoin as “a system where rules are enforced by code, not institutions,” directly aiming to solve these problems. But how can a currency have no central authority and no one to enforce the rules? How do strangers around the world agree on which digital transactions are valid without trusting a bank or government?

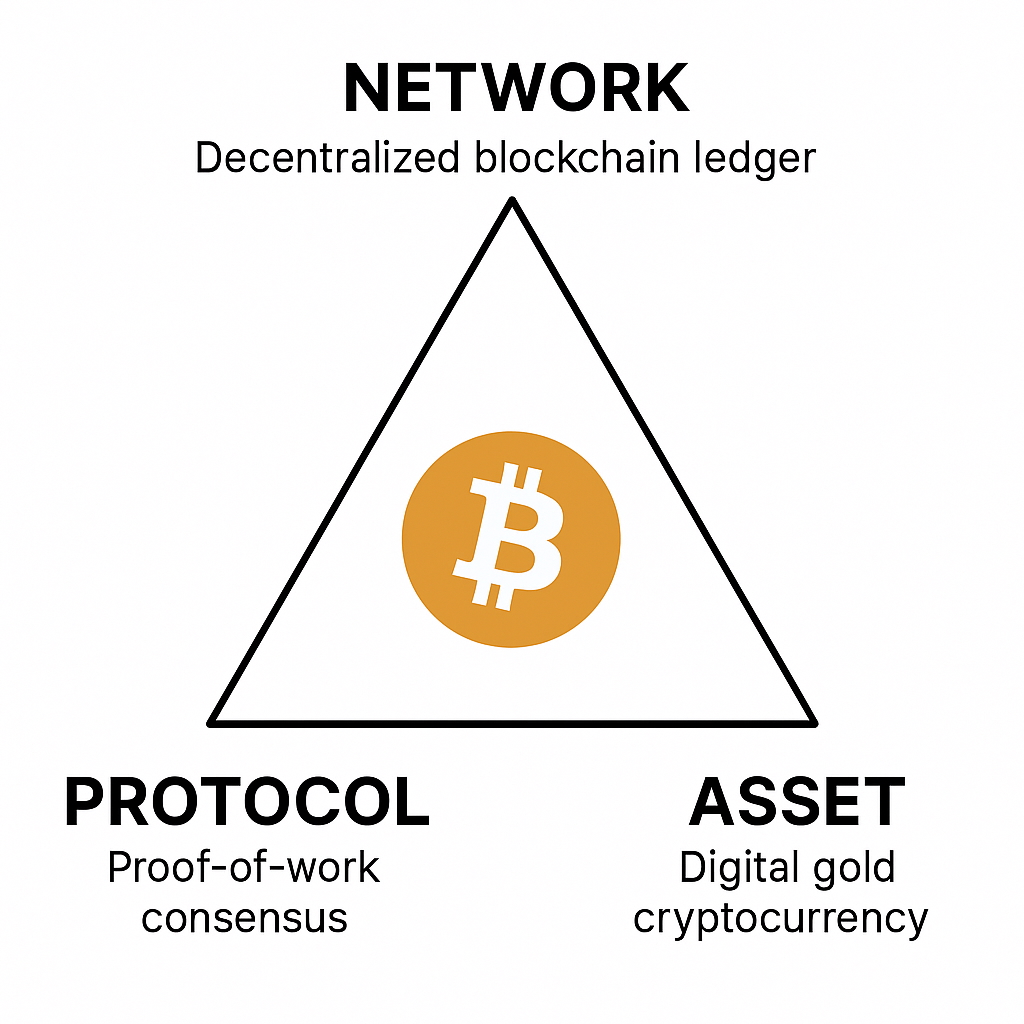

In Part 2 of our series, we’ll look under the hood at Bitcoin’s design and see how it works as a trustless, decentralized payment system. We’ll introduce Bitcoin using a three-layer framework: the network, the protocol, and the asset. Let’s dive in, starting with the Bitcoin network.

Terminology note:

-

Bitcoin (capital “B”) refers to the open‑source network‑protocol, the distributed system that records and verifies transactions.

-

bitcoin (lower-case “b”) denotes the native digital currency unit that circulates on that network (e.g., “3 bitcoin”).

Throughout this article, we’ll follow that convention to keep the roles of the network/protocol and the cryptocurrency clear.

Bitcoin as a Network: The Decentralized Blockchain Ledger

What’s a blockchain? And what’s a node?

Imagine a checkbook or a spreadsheet that everyone in the world shares and updates. That’s essentially what Bitcoin is: a global ledger of accounts and balances maintained collectively by thousands of computers. In fact, there are no physical “coins” at all. Bitcoin exists purely as entries on this distributed ledger. When Alice sends 1 bitcoin to Bob, no token jumps from her computer to his; instead, every computer in the network updates its copy of the ledger to deduct 1 bitcoin from Alice’s address and add 1 bitcoin to Bob’s. The transaction is just a recorded change in this shared database that everyone can see and verify. Each bitcoin is nothing more (or less) than a collective agreement reflected on the ledger that “Alice has X bitcoin, Bob has Y bitcoin,” and so on.

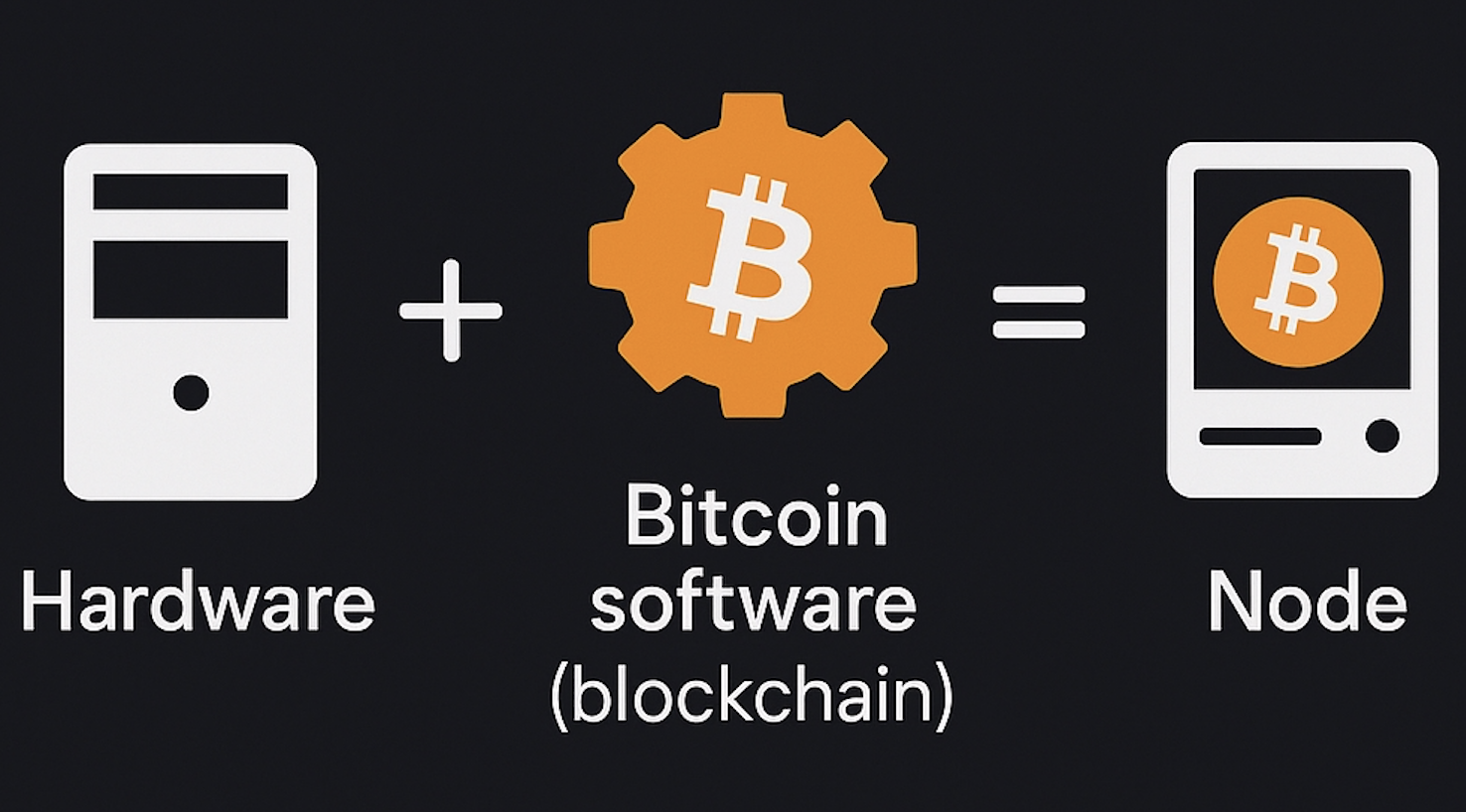

Crucially, everyone who runs the Bitcoin software has an identical copy of this ledger, known as the blockchain. When a computer runs Bitcoin software and holds a copy of this blockchain, we call this computer a “node.”

Nodes provide a single source of truth for all Bitcoin transactions. By design, the blockchain on each node is append-only. New transactions can be added as new “blocks,” but past records are extraordinarily hard to alter or erase. In essence, Bitcoin is a complete history of transactions from the very first entry (the genesis block created by Satoshi in January 2009) to the latest block added just minutes ago. This distributed ledger lays the groundwork for a financial system that any participant can audit and trust is accurate, without needing to trust any single entity. It’s a direct answer to the problem of opaque, centralized record-keeping: in Bitcoin, the records are transparent and verified by all.

Nodes make Bitcoin a peer-to-peer network and remove the need for a central authority

If Bitcoin is a global ledger, who maintains it? The answer is: everyone who participates. The Bitcoin network is a peer-to-peer (P2P) network formed by thousands of independent nodes. These nodes connect directly to each other over the internet, rather than through any central server. There is no headquarters or Bitcoin company in charge. Every node holds the full Bitcoin blockchain and follows the same rules to validate transactions. This decentralized architecture is what gives Bitcoin its resilience and trust-minimizing properties. As Satoshi Nakamoto noted when unveiling Bitcoin, “Governments are good at cutting off the heads of centrally controlled networks like Napster, but pure P2P networks like Gnutella and Tor seem to be holding their own.” In other words, a network with no single point of control cannot be easily killed or censored. If one node goes offline, nothing is lost—the remaining nodes still collectively have the ledger. There is no single “head” to cut off. Bitcoin’s pure P2P model for money means no bank or intermediary is needed to verify who owns what.

This structure makes Bitcoin borderless and censorship-resistant. Transactions spread across the network, like news through a crowd. There’s no central authority that can intercept or block a payment. Anyone with an internet connection can join as a node and help enforce the rules, whether they’re in San Diego or Singapore.

By distributing the ledger across countless peers, Bitcoin creates a system where no single entity can falsify records, seize someone’s funds, or shut the whole thing down. This directly addresses the “single point of failure” problem from Part 1: there is no central bank or company that the entire system relies on, so there’s no single point whose failure (or bad behavior) could compromise the network. A decentralized network like Bitcoin’s offers several key advantages over traditional centralized systems:

-

Resilience: There’s no central server that can fail or be attacked to bring Bitcoin down—the network routes around damage, making it extremely hard to shut off.

-

Censorship Resistance: No authority can selectively block or reverse transactions, because no one controls the ledger. The lack of a central gatekeeper means no one can “freeze” your Bitcoin or deny you access due to politics or policy.

-

Permissionless Access: Anyone can participate without needing approval from a bank or government. This open access means Bitcoin fulfills the internet’s promise of financial independence—you don’t need a trusted intermediary to send money online.

Venmo vs Bitcoin

To make this more concrete, let’s compare Bitcoin to the popular centralized payment application Venmo. Both let you send money digitally, but under the hood they work very differently.

| Feature | Venmo | Bitcoin |

|---|---|---|

| Who Controls the Ledger? | Company maintains a private ledger of balances and transactions on its servers. Users trust Venmo to update accounts correctly. | Thousands of independent nodes maintain Bitcoin’s public ledger (the blockchain) collectively. No single entity is in charge. |

| Trust and Permission | You must trust Venmo (and connected banks) to hold your funds and honor transactions. Venmo can reverse payments or freeze accounts at its discretion, and users need permission (an account, bank link, etc.) to use it. | Trustless and permissionless. Users hold their own bitcoin and transact directly. As long as you follow the protocol rules, the network will process your transaction. No account or permission is required to use Bitcoin; just a computer and internet. |

| Ledger Transparency | Only Venmo’s servers “see” the full transaction history. Users see their own balance and a social feed, but must trust Venmo’s internal records. | The entire Bitcoin transaction history is public on the blockchain. Anyone can verify balances. |

| Security & Censorship | All transactions funnel through Venmo’s systems, which could be hacked or taken down. Governments can pressure Venmo to block payments or seize funds. Users rely on Venmo’s security practices and compliance. | No central server to hack or shut down. An attacker would need to compromise the majority of the global network—which is practically impossible. Censorship is very difficult because there is no single company or country to pressure. Security comes from cryptography and network consensus rather than corporate firewalls. |

| Global Payments | Mostly limited to domestic transfers and withdrawing to a bank. Doing cross-border transfers is slower or not supported. Weekends and holidays affect when funds will settle. | Bitcoin’s global nature allows cross-border value transfer 24/7 without intermediaries, which are faster and less restrictive than traditional bank wires. |

Venmo embodies the old model: a centrally-controlled system where users must trust the middleman and live within that platform’s constraints. Bitcoin represents a new model: an open, permissionless network where users can transact with anyone, anywhere without needing to trust a third party. This doesn’t mean Bitcoin is “better” in all cases—but it offers an alternative approach to moving value, one designed to solve the very trust and control issues inherent in centralized systems.

Bitcoin as a Network, bringing it all together

By designing a network with no central authority, Bitcoin directly tackles two problems we discussed in Part 1: trust in institutions and central points of failure. There’s no bank or company that needs to be trusted to keep the ledger or facilitate transactions. The network of nodes collectively does that. And without a single controlling entity, it’s much harder for the system to fail or for any one party to abuse it.

However, a decentralized network alone isn’t enough. We still need a way for all these independent nodes to agree on which transactions to add to the ledger—in other words, a way to reach consensus on the ledger’s state. We also need a way for individuals to securely own and transfer bitcoin on this open ledger (so that only the rightful owner can spend their funds). These are challenges addressed by the Bitcoin protocol, which we’ll explore next.