Bitcoin Academy: Part 1

The Creation of Bitcoin: Centuries of Innovation and a Century-Defining Crisis

Crypto moves fast, and the pace of innovation shows no signs of slowing. Newcomers and seasoned investors alike are scrambling to keep up. Triple Point Strategy exists to cut through the noise. Our research breaks down everything from the real‑world impact of Bitcoin’s supply cap to why zero‑knowledge proofs might unlock the next wave of decentrailzed finance.

Some of you already live and breathe crypto; others have just downloaded Coinbase and are wondering why Bitcoin and Bitcoin Cash both exist. Wherever you sit on that spectrum, our goal is the same: turn complexity into clarity.

This is where Triple Point Strategy’s Academy comes in. Academy is a companion to our Insights series. Insights tackles trending crypto topics. Academy slows the pace, focusing on one landmark technology at a time. Each Academy research brief distills the mechanics, economics, and design philosophy of a single protocol into clear, approachable language. Our goal is to bring readers fully up to speed on the technology—delivering a comprehensive deep dive without the jargon or information overload.

We begin with Bitcoin Academy: a concise tour of how Bitcoin works, why it’s revolutionary, and what still makes it the cornerstone of the crypto ecosystem today.

To understand Bitcoin, we first need to explore two things:

- The core innovations that made it possible

- The catalyst that inspired its creation

Innovation 1: Money

Before Bitcoin, before banks, before even coins—there was a problem humans needed to solve: how to trade with one another.

In early societies, barter was the first solution. If you had wheat and your neighbor had fish, you could make a trade—assuming you both wanted what the other had, at the same time, in the right amounts. But barter quickly hit its limits. It’s inefficient, fragile, and depends on what's called the coincidence of wants. Put simply, both parties must want what the other is offering simultaneously.

The solution? Money: a shared medium that everyone agrees has value—not because it’s useful on its own, but because others will accept it in exchange. Over time, societies experimented with many forms of money: shells, beads, livestock, salt, stones, metal coins, and eventually paper notes. Each had to solve three basic problems:

- Store of value: it should retain worth over time

- Medium of exchange: it must be widely accepted

- Unit of account: it should allow value to be measured and compared

Eventually, precious metals like gold and silver emerged as dominant tools. They were scarce, durable, portable, and widely recognized (ideal monetary traits). But even gold had limits: it’s heavy, hard to divide, and inconvenient for daily use. That led to representative money—paper notes backed by gold or silver stored in banks.

Then came fiat currency. Today, most national currencies, such as the U.S. dollar, euro, and yen are fiat. “Fiat” means the currency has value by government decree. It isn’t backed by gold or any physical commodity. Instead, it relies on trust—trust in governments, in central banks, and in the belief that others will continue accepting it tomorrow. Fiat currencies are powerful and flexible, enabling rapid payments and broad global coordination. But they come with trade-offs: inflation risk, centralized control, and political manipulation.

As money became more digital in the 20th century, the infrastructure behind it remained largely analog. Transactions flowed through banks, clearinghouses, and closed networks. These systems were built for a pre-internet world. Moving money still required intermediaries, approvals, and access granted by gatekeepers. That began to change with the rise of the internet.

Innovation 2: The Internet

In the early days, computers were isolated machines. You could program them, store data, and run calculations, but they couldn’t communicate. That changed in the late 1960s with ARPANET, a U.S. research project that pioneered linking computers over distance—the direct predecessor of the internet. It introduced packet switching, a technique that made communication faster and more resilient.

Over the following decades, the internet evolved from a military experiment into a global communication backbone. The creation of TCP/IP in the 1980s standardized how data moved through networks. And in 1991, Tim Berners-Lee launched the World Wide Web, making it easy for anyone to browse, publish, and link information.

By the 2000s, the internet had transformed global communication, commerce, and finance. Banks launched online portals. Credit cards and payment processors moved onto the web. Financial interactions became more convenient. However, they were still centralized. Intermediaries held the keys, controlled the rules, and could revoke access at any time.

Then something new emerged: peer-to-peer protocols. Systems like Napster, BitTorrent, and Gnutella showed that decentralized networks could scale. You didn’t need a central server—just enough participants agreeing to the same protocol. Naturally, people began asking: Could we use that model to move money?

The first wave of answers was PayPal and WebMoney. These services offered faster payments, but still relied on centralized control. Accounts could be frozen, transactions reversed, access denied. Meanwhile, technologists and cryptographers began experimenting with digital cash: projects like e-gold, b-money, and Bit Gold. But these efforts struggled with technical limitations and were often shut down by regulators.

By 2008, the internet had solved global connectivity, but not financial sovereignty. You could send an email without permission. But to send money, you still had to go through a gatekeeper.

Innovation 3: Cryptography

That gatekeeping problem wasn’t just technical; it was a matter of trust. On an open network like the internet, anyone can intercept or manipulate data. Without safeguards, digital transactions could be forged, duplicated, or censored. What was needed was a way to establish trust in a trustless environment. That’s what cryptography solves.

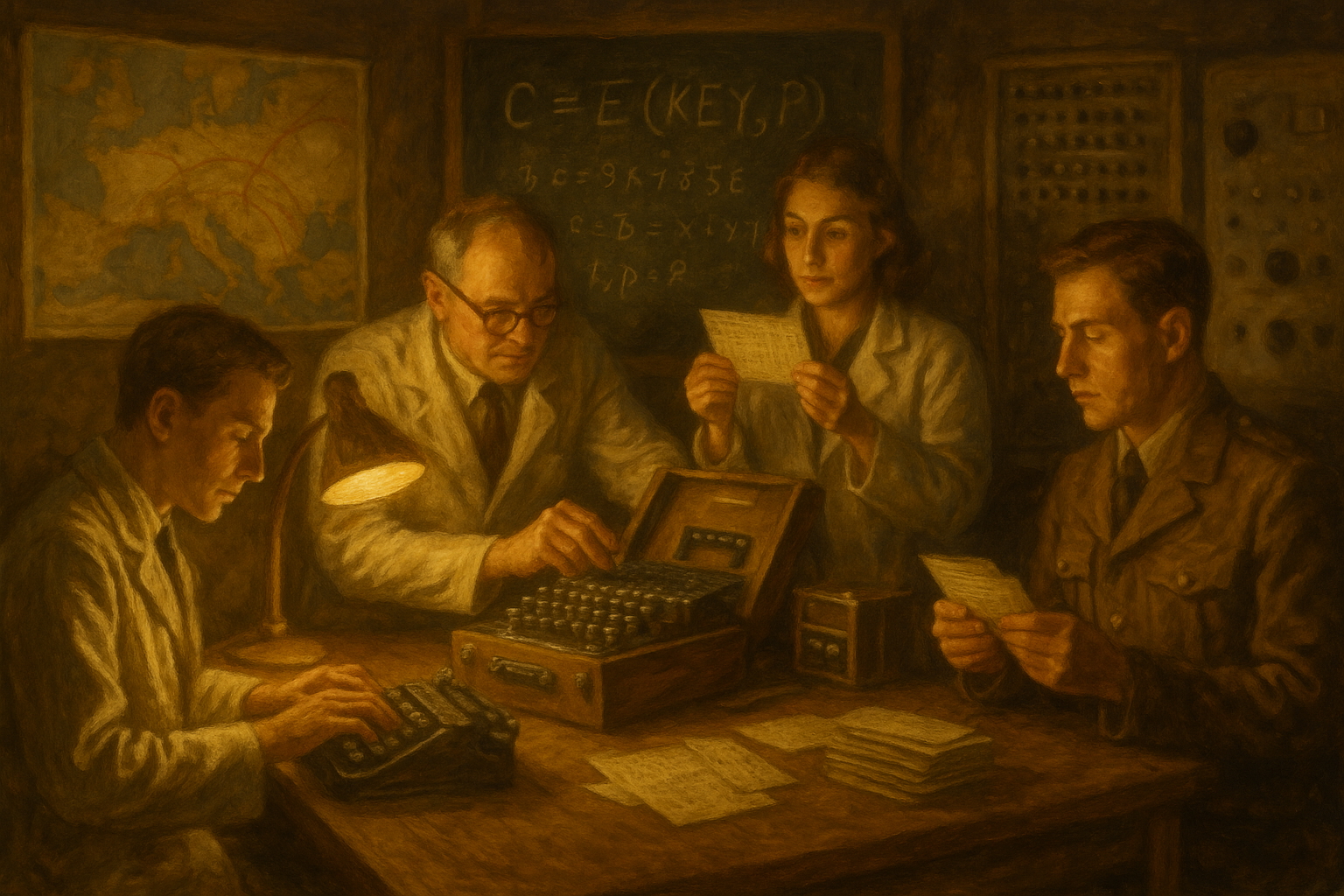

For most of history, cryptography was used to protect secrets. The Greeks used a scytale, a cylinder-wrapped parchment only readable with the right rod. Caesar used substitution ciphers to shift letters in the alphabet. These early systems relied on shared secrets: both sender and receiver had to know the “secret key.” If that key was discovered, the message, and the system, were compromised.

The 20th century changed everything. During World War II, cryptography became a scientific discipline. Germany’s Enigma machine used mechanical ciphers that rotated daily. The Allied effort to crack it, led by Alan Turing, highlighted both the power and fragility of secret-key systems.

Then came a breakthrough. In 1976, public-key cryptography was invented. For the first time, two parties could communicate securely without having exchanged a secret key. It relied on two linked keys:

- A public key, which anyone could see and use to encrypt messages

- A private key, which only the recipient held and could use to decrypt those messages

This made it possible to secure digital communication between strangers. It also enabled digital identity, authentication, and eventually secure financial transactions.

By the early 2000s, cryptography was everywhere. SSL/TLS protected websites. Passwords were hashed and encrypted. Banks secured user data. And governments used cryptography for both defense and surveillance.

Meanwhile, the cypherpunks—a group of privacy-focused technologists—were exploring a more radical vision. They saw cryptography not just as a tool for safety, but as a weapon against centralized power. It offered a way to enable individual freedom in the digital age.

By 2008, all the core cryptographic tools were in place. But no one had yet woven them into a fully decentralized currency. The final step was still missing—inspiration.

The Catalyst: The 2008 Financial Crisis

By the end of 2008, the stage was set.

- We had money, but it was centralized and politically vulnerable.

- We had the internet, but it hadn’t delivered financial independence.

- We had cryptography, but it hadn’t yet replaced institutional trust.

Then came the spark: the global financial crisis. Centuries-old banks collapsed. Governments rushed to issue bailouts. Millions lost jobs, homes, and savings. The trust-based financial system—the one people assumed was stable—revealed its cracks. Somewhere in the midst of that chaos, a person or group using the alias Satoshi Nakamoto published a whitepaper: “Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System.” On January 3, 2009, the Bitcoin network launched. Embedded in its first block was a message:

“The Times 03/Jan/2009 Chancellor on brink of second bailout for banks.”

It referenced the front-page headline of The Times from the United Kingdom, reporting that the British government was preparing to bail out major banks for the second time. The quote wasn’t just a timestamp; it was a statement of intent. It was a subtle but powerful indictment of a failing financial system.

Over the following months, Satoshi corresponded with early Bitcoin contributors. The message was consistent: Bitcoin was not about profit or hype. It was about building a system that didn’t require trust in banks, corporations, or governments. “The root problem with conventional currency is all the trust that’s required to make it work,” Satoshi wrote in 2009. “The central bank must be trusted not to debase the currency, but the history of fiat currencies is full of breaches of that trust.”

Bitcoin wasn’t born out of academic curiosity. It was a response to failure. It was a proposal for a system in which rules are enforced by code, not institutions.

What’s Next

In our next post, we’ll explore how these three innovations—money, the internet, and cryptography—came together in Bitcoin’s design. We’ll look under the hood at how Bitcoin works, and how a decentralized network of people, companies, and nations can enforce a shared monetary system without ever trusting one another.